Today we begin a series on the changing pattern of Maori land use and ownership. Historian Bruce Moon has done extensive research on this topic and sets out to dispel misunderstandings about what has often been a contentious area.

Bruce Moon, all of whose pioneer ancestors arrived in New Zealand before 1880, was a himself a pioneer in computing and information technology. In retirement he has done voluntary work in Vanuatu and India. More recently his studies of our history have revealed that there is much that is false in the official version taught in schools and universities.

Plenty of food for the taking

By Bruce Moon

Isolated from the rest of the world for several centuries, the pre-European Maoris of New Zealand lived in a Stone Age hunter-gatherer society, albeit kumara and some minor crops were grown in the north.

Isolated from the rest of the world for several centuries, the pre-European Maoris of New Zealand lived in a Stone Age hunter-gatherer society, albeit kumara and some minor crops were grown in the north.

Inshore fishing and what they could gather from the bush were their main food sources. Fern-root, nutritious but fibrous and hard on teeth, was the major plant source while the lack of large land animals meant that apart from the Maori rat, the kiore, birds were the source of animal protein.

With no idea of conservation, despite recent claims to the contrary, birds were hunted ruthlessly, around thirty species being driven to extinction before Europeans arrived[i], one a unique black swan only just identified,[ii] and the various kinds of moa in barely a century.

As examination of ancient middens has revealed, that often only the choice cuts were eaten, and much of a moa carcass went to waste.

Cannibalism and inter-tribal warfare

While the practice of cannibalism was probably brought to New Zealand by Polynesian immigrants, depletion of other food sources made it an attractive option.

By time Europeans arrived it was well-established, as vividly shown by the 1772 fate of Marion du Fresne and 26 of his crew, promptly massacred and eaten for fishing innocently in a “tapu” bay.[iii]

As hunter-gatherers, each tribe needed a hunting area or “rohe” of its own but as intertribal warfare was their favourite sport, this meant incursions into the rohe of another tribe and often its acquisition by conquest. The process has been described by Michael King in “Moriori”[iv] with eyewitness accounts of those events, a mere five years before the Treaty was signed. “[V]ictims were killed by a blow … to the temple. Afterwards, … the

heads were removed and thrown to the dogs … Then the virile member [penis] … was thrown to the women … who ate this dainty morsel eagerly.” The remainder of the body was then dismembered, washed and cooked in a “hangi”.

As King continues: “[W]hat took place was simply tikanga, the traditional manner of supporting new land claims. As Rakatau noted with some satisfaction in the Native Land Court in 1870: ‘ we took possession … in accordance with our customs … .’ … The outcome was nothing more nor less than what had occurred on battlefields throughout the North Island.”

By contrast and as far as I know, not a single Maori was killed and eaten by any settler from Britain as part of the process of obtaining land.

New foods and an eagerness to sell land

Now, hunter-gathering means that food sources are where one finds them and this is most successful when a band of individuals works together. This implied in turn that the rohe, the food-gathering area, was not held by individuals but in common by tribal members, sharing the proceeds but doing little, if anything, to improve it as a food source.[1]

Apart from the kumara plots, it was not farmed.

It is this obsolete form of land-holding which continues under Maori title today.

This was the situation which Europeans found when they showed an interest in buying land.

Maoris on the other hand, soon began to appreciate the superior and more readily produced food which Europeans brought.

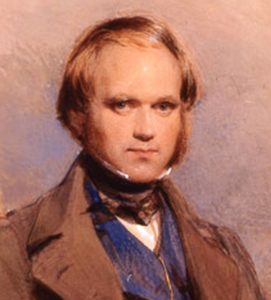

Notable were pork and potatoes, described with timber and flax as their only “taonga” by 13 Ngapuhi chiefs writing to King William in 1831. When Charles Darwin, prince of observers, arrived on the 1835 visit of HMS “Beagle”, he noted on his walk to the Waimate mission in Northland: “The road [was] bordered on each side by tall fern … we came to a little country village, where a few hovels were collected together, and some ground cultivated with potatoes.

Suddenly the tribes discovered that large hunter-gathering areas were no longer necessary for their support, while the variety of material goods and possessions of Europeans were attractive items much to be desired.

A rapid transformation occurred of the entire tribal system of values. A veritable frenzy of land selling began, some chiefs travelling to Sydney to sell.

Of course they encountered plenty of speculators ready to deal with them. The documents recording the transactions exist there today.

Footnotes

[1] An exception was the extensive area of eel-trapping weirs near the Wairau River mouth, possibly constructed by pre-Maori inhabitants.

[i] Tm Flannery’s estimate is 28-35. In 1883, Maoris are known to have killed 646 Huia in a single month.

[ii] Nick Rawlence, Prime News, 26th July 2017

[iii] Ian Wishart, “The Great Divide”, HATM Publishing, 2012, Ch. 3, ISBN 978-0-9876573-6-7

[iv] Michael King, “Moriori”, Viking, 1989, pp. 64-66, ISBN 978-0-670-82655-3

[v] Charles Darwin, “The Voyage of the Beagle”, 1839

Bruce is just so clear and accurate! Reading his writing is like rain in the desert!

I admire both Bruce Moon and the Kapiti Independent News for being among a small number of honest historians and media outlets prepared to tell — and allow to be told —the truth about our country’s past.

But how sad that Cultural Marxism has become so pervasive in New Zealand that an act of honesty should need to be singled out for praise.

I’ve come to this series months late and can confirm for others that Parts 2, 3 and 4 are every bit as compelling and factual as Part 1.

If only certain academics and lawyers knighted for peddling lies placed as much of a premium on historical evidence as Bruce Moon.